We look forward to seeing you there!

Please register ahead of time at tinyurl.com/birdypoetry2022,

and find all the other details here...

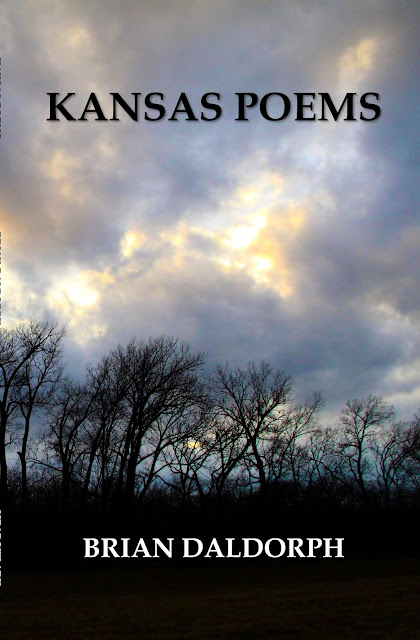

To add to the festivities leading up to the event, we would like to take a moment to revisit our 2020 Birdy Poetry Prize finalist, Kansas Poems by Brian Daldorph. Not only can you find excerpts of the book and videos of Brian reading, but now, we get to share this review of the poetry collection, written by Meadowlark Publicist Linzi Garcia.

Connecting in Kansas: Brian Daldorph’s Kansas Poems

The winters of 2020 and 2021 were brutal. With record highs of COVID-19 infections and deaths and record low temperatures across the nation, those of us who could endured, created, and shared what we had, both in supplies and craft. We developed virtual communities to connect with one another that thrived beyond conventional place and time.

In a world where place and time blurred, poets including Brian Daldorph saw the circumstances as an opportunity. He released Kansas Poems (Meadowlark 2021), a poetry collection that tells stories collected over the last twenty years that Daldorph has resided in Kansas. The collection takes readers from near and far on a stroll down the KU frat house road, through Oak Hill Cemetery, onto Daldorph’s front porch, and clear across The Flint Hills. This book was the touch of warmth readers needed to help carry them into spring.

The poetry collection, organized into seasons, starting with spring, opens with the poem “Unfreezing,” an appropriate entry into a season of rebirth and celebration of the new book:

First daffodils

outside City Hall

facing south. Spray

of crocuses

in the front yard of 829 E. 13th.

And in his heart?

All the flowers of spring

waiting

only for warmth (3).

The book transcends the confines of time by connecting present-day Kansans and readers with preceding and future generations. In “Sailing to Manhattan, Kansas,” the characters observe the timelessness of the rocky landscape one summer day:

We look out together at the still

green waves of the Flint Hills--

“We’re seeing the same thing people saw

hundreds of years ago--

This land’s too wild to be tamed.

Might as well try to chain the sea” (27).

Environmental seasonal changes are distinct in Kansas, and its towns and people often move in parallel with them. The Fall section opens with the poem, “Cooper City,” describing how a once-thriving rural town has fallen victim to the passing of time:

Storefronts Boarded up

but Jack’s Autos is still there

with rustbuckets, non-starters

and crooked Jack who left

half a leg and most of his soul in Vietnam.

…

Main Street’s a few hand-me-down stores,

some sleepy attorneys,

and Zeke Haskins, Undertaker,

with old Zeke in the window wondering

days on end if he or Cooper Citywill go first (51).

As with all life, death follows. There is a subtle melancholic tone throughout the book, built on the understanding that we will experience loss in a variety of ways throughout our lives, and often those losses haunt us.

In the poem, “Visiting Findley,” the loss at hand is not that of death or disappearance, but that of change of character and relationship, because the son, Findley, is incarcerated. Daldorph writes from Findley’s father’s perspective:

I imagine visiting him with his pretty wife and first child. With

ten years carved out of his life how’s he going to achieve

anything like that? Who’d want to marry an ex-con?

It takes me half an hour to get through security and ten doors

later I’m in the meeting room, a row of cubicles with chairs in

front of glass screens.

I sit in my place and wait for Findley, for my son gone wrong,

my tattooed, hard-eyed son, the son I tried to love but didn’t

love enough, the son who never made it easy.

I wait for my son (19).

One aspect of what makes this book dynamic is the variety of perspectives from which Daldorph writes. Telling the story of the deserted wife (“Missing Husband” 7), Paleontologist Handel T. Martin (“The Fossil Man” and others 21-24), and a june bug (“June Bug” 43), among others’, from the character’s perspectives shows Daldorph’s expert craft and reinforces that this collection shares Kansans’ and Kansas’ stories in their voices, both apart from and including Daldorph’s own experiences.

The book guides the reader out of its pages during winter, beginning this season’s section with “First Snow”:

I stayed up late

watching snowflakes fall,

writing haiku. Then

I went to sleep,

dreamt of snow

covering me

in Oak Hill Cemetery

like a warm white shroud (71).

It is a simple, tranquil understanding of the movement of life to death. The winter section, and the book, concludes with a February estate sale—a last hint of what remains after death, before the next rebirth of spring.

Kansas Poems accomplishes a thorough journey across Kansas, and the virtual book launch event proved how readers from across place and time want to be a part of that journey. Though the event took place for Daldorph at 6 p.m. in Lawrence, many of his guests attended internationally in the middle of the night.

Some of what happens in Kansas is unique to Kansas and Kansans—digging up “the great Kansas Rhinoceros,” for example (24). Some of what happens in Kansas is a microcosm of what happens everywhere and to everyone, such as the realization of growing up. This book is both unique and relatable—a necessary balance to appeal to a wide audience.

Whether living across an ocean or just a few doors down from the poet, Kansas Poems provides the opportunity to connect with the place that captivated Daldorph and his muses.

***

Listen to Brian read this Friday!

***

.png)